“The talent of staying calm under pressure is the singular thing that separates good from great” – John Brenkus

Hi everyone,

I thought for this post we’d focus on an interesting article I recently read. I’ll link to it below.

The premise of this article is that we can train ourselves psychologically in order to perform better in stressful situations.

In other words, there are ways to train our minds and bodies that help us under pressure.

I couldn’t agree more.

I’ve been practicing mindfulness/meditation for almost twenty years. Personally, I’ve seen the massively positive impacts on my life and on my practice of medicine. Simply, I just don’t react to stressful situations the way I once did.

The authors argue that we can train ourselves in psychological skills in order to perform better under acute stress. And that this is something that is fundamentally lacking in our training.

Professionally, I practice full-time emergency medicine in a large urban environment with trainees. Often I’m involved in practice examinations and mock (and real) resuscitation scenarios. It’s clear to me that the majority of our training in resuscitation is focused on the content. Meaning, we’re mostly worried if we’ve chosen the correct drugs with the appropriate doses, given in the right order for the right diagnosis. Of course, knowing that information is incredibly important.

But, our cognition during resuscitation is frequently glossed over. And often never discussed.

It’s important to discuss additional ways we can improve our performance. Especially once we’ve learned the core content. Learning and practicing psychological skills can be another way to help us function better. These are not esoteric skills primarily of use by yogis. They are used by other occupations including high-performance athletes, the military, and even astronauts. So, why not us?

Stress and performance

We know that stress negatively impacts our performance. Imagine, how you’d perform in a situation in which you’re overly stressed out, compared to one in which you’re focused and in control. When you’re in control, you perform better.

Acute stress can create numerous performance deficits. For instance, it can impact our ability to store information in our short-term memory, effect our decision-making ability and makes it difficult for us to communicate effectively. A little bit of stress might actually help us to get into focus, but a hyper-sympathetic response to a situation and it all falls apart.

In the paper, the authors state that acute stress is a result of two major factors – perception and compensation.

Perception

Perception is essentially how we approach a situation. How do you approach an acute, emergency event in medicine? What are the thoughts, ideas, and feelings that are going through you as you approach the situation? Have you ever paid attention? Or for that matter have you observed how junior learners approach a similar situation and do you notice a difference between you and them?

In my environment, we often get called to the resuscitation bay and have a couple minutes to prepare for “something bad” coming in. We often don’t even know what is about to arrive.

In those couple of minutes, what might be going through your head?

Sure, some of it for sure is making sure you’re prepared for the situation ahead. Do you have the right people, equipment, and drugs. But what other messaging is going on? Are you feeling confident about the situation? Scared? Absolutely mortified? What kinds of things do you tell yourself? Have you ever noticed?

The authors note that how you view the upcoming situation can impact your response to it. This is something to notice and possibly retrain.

Compensation

Compensation involves the mechanisms one uses to cope with an acutely stressful situation. These are usually modalities that are either pre-existing or learned. The better your coping mechanisms, the less likely you are to amplify a stressful response to a situation.

Do you have some ways in which you are able to keep yourself calm when things get stressful? What strategies are in place and how do you use them?

Intervention

The authors focus on steps one can train and take in and around an acute stressful medical event. They call this training performance-enhancing psychological skills or PEPS for short.

“PEPS are specifically designed to empower people to actively address their emotional state and take steps to mitigate their stress response in real time. Controlling and managing responses to acutely stressful medical emergencies may allow providers to maintain situational awareness, think clearly, recall important information quickly, act decisively, and perform skills efficiently.”

The application of PEPS is something that can be used as an adjunct to the clinical training we already receive. While we’re doing simulation training and going through cases and scenarios, we can also practice controlling our responses to managing those cases. This would help train us to manage ourselves in the moment.

For this article, PEPS consists of into 4 distinct psychological skills.

Breathing

The ability to notice and then consciously control our own respiratory state can have a calming impact our emotional state.

We know that respiration is the only autonomic function that we have conscious control over. When we are able to slow down our breathing, our pulse often slows and we can feel instantly more at ease.

Making sure that we take time to take a few slow, deep breaths before and during breaks in a resuscitation can help us decrease our arousal response to stress. It’s something to consider when you’re overwhelmed. For instance, during a pulse check during a cardiac arrest situation, can you also take a moment to remember to take two slow, deep breaths?

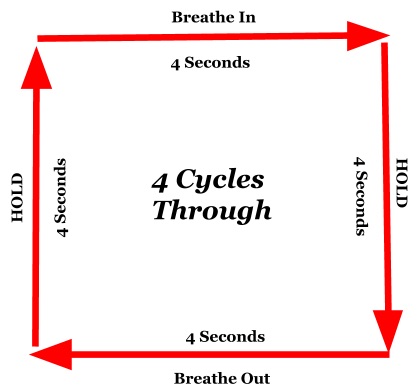

Box breathing is a commonly used method to help slow one’s breathing. Essentially, breathing is broken down into four parts, represented by a square.

Inhalation, a pause, exhalation and another pause.

Each side of the square is given a four second interval and the sequence is repeated as many times as necessary.

Personally I use this technique all the time. Sometimes before bed, or during (or just after) a stressful event at work. Other times just as a little reset. It definitely works to help me feel calm in the moment and gets my focus outside of my head and into my body. I also often give this to patients with acute anxiety or panic disorder that present to the ER. It’s a simple intervention that gives them a tangible tool that they can practice while they wait for me to return.

Self – Talk

Our inner voice, or the things we say to ourselves can also be harnessed to improve our performance.

To repeat, you can actually improve how you perform in a task, by learning how to talk to yourself in a way that encourages you to succeed.

There are different ways to positively self-talk.

The authors mention instructional varieties – for instance with intubation saying to yourself “find the epiglottis, blade into vallecula, pull up”.

Motivational self-talk consists of saying things like “I got this” or “I can do this”.

The greater point is that finding phrases that are easy to remember and are kindly worded can be a way to reassure yourself mentally that you are ready for a challenging task ahead. So think of a few words of encouragement and don’t be afraid to use them when you’re in a stressful situation. You got this!

Visualization

Using visual imagery to work your way through the mental steps of a task can also be a helpful way to enhance your performance.

We know that athletes frequently mentally rehearse the movements required for their performance, and that this actually has been shown to lead to an improved performance. So why not doctors?

Instead of just simulating a resuscitation scenario in a high-fidelity setting, we can also just go through the mental steps of these high-acuity, low-volume scenarios. In emergency medicine cricothyroidimy, transvenous pacemaker insertion, and a lateral canthotomy are examples of such procedures.

The more specifically we can visualize the scenario, the more effective the technique. For resuscitation, can you visualize the room? The monitors? The patient? The team? The equipment? Can you imagine how you might feel?

If you’re trying to visualize a procedural task can you go through the procedure in a step-by-step fashion? What are all the little details that will help this procedure go smoothly? Can you rehearse all of this before going through with the actual task?

Trigger word

The final technique involved the use of a trigger word. This can be a simple word, or statement that helps the provider refocus on the task at hand. It’s a little reminder of what you’re about to do and can be used as a tool to stay focused.

Triggers words can be anything, but the authors use examples of simple statements like “smooth” or “focus”. Again, the key here is that it provides a mental reminder to refocus and can help avoid the mistake of getting too fixated on one particular task.

A similar technique is used in mindfulness practice and is called labeling. It’s a similar concept where you send yourself a reminder of what you’ve decided to focus on, and you repeat that label to yourself to reset your attention. For instance, if you’re focusing on sounds in your room, you repeat the mental label “Hear” every 5-10 seconds, or when you’ve noticed that you’ve lost attention. In my experience, this is a simple and powerful way to keep your attention on something narrow.

So why do this?

We have stressful jobs in medicine. Sometimes we have to make critical decisions in a moments notice.

We don’t often consider how our internal state affects our ability to make snap decisions under stress. There’s lots of evidence that acute stress affects our cognition in many important ways that keep us from acting optimally.

Additionally, many of us don’t realize that we can manage our internal states and improve our responses through practice. With practice, you can learn to be aware of your own internal state and implement strategies that can help you remain clear and calm. This is something we can train.

Not only would this have value to you and how you feel, but this would be tremendously important to the people you treat.

Using these PEPS methods is one way to help mitigate the acute stress response, and help you be at your best under stress. Why not give it a try. Or train your students. The better we all feel, the better we will perform.

1 comment

These are great techniques. I use the breathing technique as well; however I use one I saw from Tony Robbins. Inhale for 7 seconds, hold for 28 seconds and exhale for 14 seconds, great for relaxing the body and mind.